The boy who saw the Virgin Mary: the miracle of Bronx

The vision came a few months after the end of the Second World War. Loads of joyful military men were returning to the city from abroad. New York was indisputably self-confident. "All the signs were that it would be the supreme city of the western world, or even the world as a whole," wrote Jan Morris in his book "Manhattan '45". The New Yorkers, he added, using a phrase from an optimistic corporate booklet of the time, saw themselves as a people "to whom nothing is impossible".

This particular impossibility, the vision, soon vanished from the headlines. The archdiocese of New York refused to issue a statement on its validity and with the passing of days, months and years, local Roman Catholics have forgotten the "Bronx Miracle", as Life magazine called it. But the young Joseph Vitolo has never forgotten, neither during the Christmas period nor in other seasons of the year. He visited the place every evening, a practice that drove him away from friends in his Bedford Park neighborhood who were more interested in going to Yankee Stadium or Orchard Beach. Many in the working class area, even some adults, laughed at him for his pity, derisively calling him "St. Joseph."

Through years of poverty, Vitolo, a modest man who works as a janitor at the Jacobi Medical Center and prays that his two grown daughters find good husbands, has maintained this devotion. Whenever he tried to start a life away from the place of the apparition - he tried twice to become a priest - he found himself attracted to the old neighborhood. Today, sitting in his creaky three-story house, Mr. Vitolo said that the moment changed his life, made him better. He has a big and precious scrapbook about the event. But his life peaked at an early age: what could compete? - and there is a tiredness, a guard around him,

Have you ever questioned what your eyes have seen? "I never had any doubts," he said. “Other people have done it, but I haven't. I know what I saw. " The fabulous story began two nights before Halloween. The newspapers were full of stories about the destruction that the war had wrought in Europe and Asia. William O'Dwyer, a former district attorney of Irish descent, was a few days after his election as mayor. Yankee fans complained about their team's fourth place; its main hitter had been second base Snuffy Stirnweiss, not exactly Ruth or Mantle.

Joseph Vitolo, the child of his family and small for his age, was playing with friends when suddenly three girls said they saw something on a rocky hill behind Joseph's house, on Villa Avenue, one block from the Grand Concourse. Joseph said he hadn't noticed anything. One of the girls suggested that he pray.

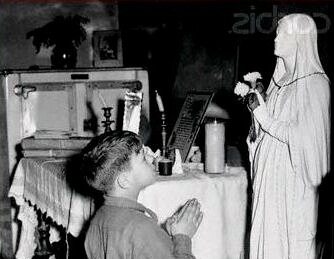

Whispered a Our Father. Nothing happened. Then, with greater sentiment, he recited an Ave Maria. Immediately, he said, he saw a floating figure, a young woman in pink who looked like the Virgin Mary. The vision called him by name.

"I was petrified," he recalled. "But his voice calmed me."

He approached cautiously and listened as the vision spoke. He asked him to go there for 16 consecutive nights to pronounce the rosary. He told him that he wanted the world to pray for peace. Not seen by other children, the vision then disappeared.

Joseph rushed home to tell his parents, but they had already heard the news. His father, a rubbish bin who was an alcoholic, was outraged. He slapped the boy for telling lies. "My father was very tough," said Vitolo. “He would have beaten my mother. It was the first time that struck me. " Mrs. Vitolo, a religious woman who had had 18 children, of whom only 11 survived childhood, was more sensitive to Joseph's story. The following night he accompanied his son to the scene.

The news was spreading. That evening, 200 people gathered. The boy knelt on the ground, began to pray and reported that another vision of the Virgin Mary had appeared, this time asking everyone present to sing hymns. "While the crowd worshiped outdoors last night and lit cross-shaped votive candles, ... at least 50 motorists stopped their cars near the scene," wrote George F. O'Brien, a reporter for The Home News , the main Bronx newspaper. "Some knelt by the sidewalk when they heard of the meeting occasion."

O'Brien reminded his readers that Joseph's story was similar to that of Bernadette Soubirous, the poor shepherdess who claimed to see the Virgin Mary in Lourdes, France, in 1858. The Roman Catholic Church recognized her visions as authentic and eventually declared her a saint, and the 1943 film about her experience, "Song of Bernadette", won four Oscars. Joseph told the reporter he hadn't seen the film.

In the next few days, history jumped completely into the spotlight. The newspapers published photographs of Joseph kneeling piously on the hill. Reporters of Italian newspapers and international transfer services appeared, hundreds of articles circulated all over the world and people wishing for miracles arrived at the Vitolo house at all hours. "I couldn't go to sleep at night because people were constantly at home," said Vitolo. Lou Costello of Abbott and Costello sent a small statue enclosed in glass. Frank Sinatra brought a large statue of Mary which is still in Vitolo's living room. ("I just saw him behind," said Vitolo.) Cardinal Francis Spellman, archbishop of New York, entered Vitolo's house with a retinue of priests and spoke briefly with the boy.

Even Joseph's drunk father viewed his youngest child differently. "He said to me, 'Why don't you heal my back?' He remembered Signor Vitolo. "And I put a hand on his back and said," Dad, you're better. " The next day he returned to work. "But the boy was overwhelmed by all the attention." I didn't understand what it was, "said Vitolo." People accused me, sought help, looked for treatment. I was young and confused. ”

By the seventh night of the visions, over 5.000 people were filling the area. The crowd included sad-faced women in shawls touching the rosary; a contingent of priests and nuns who have been given a special area to pray; and well-dressed couples who had come from Manhattan by limousine. Joseph was brought to and from the hill by a voluminous neighbor, who protected him from sovereign worshipers, some of whom had already torn the buttons from the boy's coat.

After the services, he was placed on a table in his living room like a slow procession of the needy parades before him. Unsure what to do, he put his hands on his head and said a prayer. He saw them all: veterans injured on the battlefield, old women who had difficulty walking, children with injuries in the schoolyard. It was as if a mini-Lourdes had arisen in the Bronx.

Not surprisingly, miracle stories quickly emerged. Mr. O'Brien told the story of a child whose paralyzed hand was repaired after touching the sand from the site. On November 13, the penultimate evening of the prophesied apparitions, more than 20.000 people showed up, many via buses hired from Philadelphia and other cities.

The last night promised to be the most spectacular. Newspapers reported that the Virgin Mary had told Joseph that a well would miraculously appear. The anticipation was at the height of the fever. When a light rain fell, between 25.000 and 30.000 settled for service. Police have closed a section of the Grand Concourse. The rugs were placed on the path that led to the hill to prevent pilgrims from falling into the mud. Then Joseph was delivered to the hill and placed in a sea of 200 flickering candles.

Wearing a shapeless blue sweater, he began to pray. Then someone in the crowd shouted, "A vision!" A wave of excitement crossed the rally, until it was discovered that the man had glimpsed a spectator dressed in white. It was the most compelling moment. The prayer session continued as usual. After it was finished, Joseph was taken home.

"I remember hearing people scream as they were bringing me back," said Vitolo. “They were shouting: 'Look! Look! Look!' I remember looking back and the sky had opened. Some people said they saw the Madonna in white rise into the sky. But I only saw the sky open up. "

The intoxicating events of autumn 1945 marked the end of Giuseppe Vitolo's childhood. No longer a normal child, he had to live up to the responsibility of someone who had been honored by a divine spirit. Then, every evening at 7, he respectfully walked up the hill to recite the rosary for the progressively smaller crowds who were visiting a place that was being transformed into a sanctuary. His faith was strong, but his constant religious devotions made him lose friends and hurt in school. He grew up in a sad and lonely boy.

The other day, Mr. Vitolo was sitting in his large living room, remembering that past. In one corner is the statue that Sinatra brought, one of his hands damaged by a piece of fallen ceiling. On the wall is a brightly colored painting of Mary, created by the artist according to the instructions of Mr. Vitolo.

"People would make fun of me," said Vitolo of his youth. "I was walking on the street and adult men shouted:" Here, St. Joseph. "I stopped walking down that street. It was not an easy time. I suffered. "When his beloved mother died in 1951, he tried to give direction in his life by studying to become a priest. He left Samuel Gompers' professional and technical school in the South Bronx and enrolled in a Benedictine seminary in Illinois. But it quickly tightened on experience. His superiors expected a lot from him - he was a visionary after all - and he got tired of their high hopes. "They were wonderful people, but they scared me," he said.

Without purpose, he signed up for another seminar, but that plan also failed. He then found a job in the Bronx as an apprentice typographer and resumed his nocturnal devotions at the sanctuary. But over time he got annoyed by responsibility, fed up with crackpots and sometimes resentful. "People asked me to pray for them and I was looking for help too," said Vitolo. "People asked me: 'Pray that my son will enter the fire brigade.' I would think, why can't someone find me a job in the fire department? "

Things started to improve in the early 60s. A new group of worshipers took an interest in his visions and, inspired by their pity, Signor Vitolo resumed his dedication to his encounter with the divine. He grew up next to one of the pilgrims, Grace Vacca of Boston, and they married in 1963. Another worshiper, Salvatore Mazzela, an auto worker, bought the house near the apparition site, ensuring its safety from the developers. Signor Mazzela became the guardian of the sanctuary, planting flowers, building walkways and installing statues. He himself had visited the sanctuary during the apparitions of 1945.

"A woman in the crowd said to me: 'Why did you come here?'" Recalled Mr. Mazzela. “I didn't know what to answer. He said, 'You came here to save your soul.' I didn't know who he was, but he showed me. God showed me. "

Even in the 70s and 80s, as much of the Bronx was overcome by urban degradation and balloon crime, the small sanctuary remained an oasis of peace. It has never been vandalized. In these years, most of the Irish and Italians who had attended the sanctuary moved to the suburbs and were replaced by Puerto Ricans, Dominicans and other Catholic new arrivals. Today, most passersby know nothing of the thousands of people who once gathered there.

"I've always wondered what it was," said Sheri Warren, a six-year-old resident of the neighborhood, who had returned from the grocery store on a recent afternoon. “Maybe it happened a long time ago. It's a mystery to me. "

Today, a statue of Mary with the glass enclosed is the centerpiece of the sanctuary, raised on a stone platform and placed exactly where Mr. Vitolo said the vision appeared. Nearby are wooden benches for worshipers, statues of Archangel Michael and the Infant of Prague and a tablet-shaped sign with the Ten Commandments.

But if the sanctuary remained viable for those decades, Mr. Vitolo fought. He lived with his wife and two daughters in the ramshackle Vitolo family home, a creamy three-story structure a few blocks from the church of San Filippo Neri, where the family has long loved. He worked in various humble jobs to keep the family out of poverty. In the mid-70s, he was employed at Aqueduct, Belmont and other local racecourses, collecting urine and blood samples from horses. In 1985 he joined the staff of the Jacobi Medical Center in the northern Bronx, where he still works, stripping and waxing the floors and rarely revealing his past to collaborators. "As a boy I was quite ridiculous"

His wife died a few years ago and Mr. Vitolo has spent the last decade worrying more about the bills for heating the house, which he now shares with a daughter, Marie, rather than increasing the presence of the sanctuary. Next to his house there is an abandoned and scattered playground; across the street is Jerry's Steakhouse, which did spectacular business in the fall of 1945 but is now empty, marked by a 1940's rusty neon sign. Vitolo's dedication to his sanctuary still persists. "I tell Joseph that the authenticity of the sanctuary is its poverty," said Geraldine Piva, a devoted believer. "IS'

For his part, Mr. Vitolo says that a constant commitment to visions gives meaning to his life and protects him from the fate of his father, who died in the 60s. He is excited every year, he says, since the anniversary of the apparitions of the Virgin, which is marked by a mass and celebrations. The sanctuary devotees, who now number about 70 people, travel from different states to participate.

The aging visionary has flirted with the idea of moving - perhaps to Florida, where his daughter Ann and two of his sisters live - but cannot leave his sacred place. Her creaking bones make it difficult to walk to the site, but she plans to climb as long as possible. For a man who has struggled for a long time to find a career, the visions of 57 years ago have proved to be a calling.

"Maybe if I could take the shrine with me, I'd move," he said. “But I remember, on the last night of the visions of 1945, the Virgin Mary did not say goodbye. It has just left. So who knows, one day she might be back. If you do, I'll be here waiting for you. "