the Church shows the ministry of creativity during pandemics

Aside but together: the Church shows the ministry of creativity during pandemics

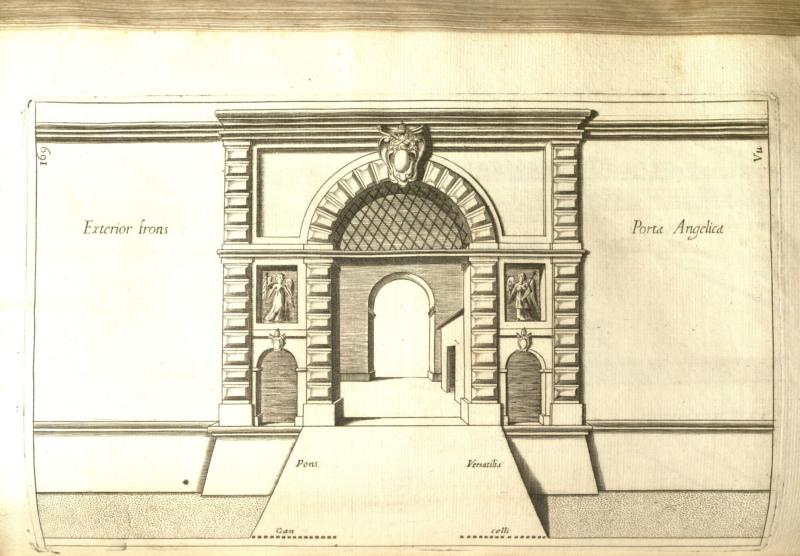

The Porta Angelica, a door near the Vatican which was demolished in 1888, is depicted in the manual of Cardinal Girolamo Gastaldi from 1684 with guidelines for responding to a plague. The cardinal's guidelines were based on his experience during the plague of 1656, when Pope Alexander VII commissioned him to manage the lazaros in Rome, where people were separated for isolation, quarantine and recovery. (Credit: CNS Photo / Courtesy Rare Book Collection, Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School.)

ROME - The Catholic Church's acceptance of a collection ban for public worship and following other painful restrictions COVID-19 reflects its longstanding understanding that faith, service and science are not in conflict with each other.

The church has had centuries of experience with do's and don'ts during a pandemic - and far from being an antagonist, it has often been at the forefront of supporting public health measures considered at the time to be the most effective at containing the infection.

One of the most important series of public health guidelines for quarantine was published by Cardinal Girolamo Gastaldi in 1684.

The nearly 1.000-page folio has become "the main manual for the response to the plague," wrote Anthony Majanlahti, a Canadian historian and author specializing in the social history of Rome.

The "advice of the manual seems very familiar in today's Rome: protect the doors; keep quarantine; watch over your people. In addition, nearby sites of popular aggregation, from taverns to churches, "he wrote in an online article of April 19," A history of illness, faith and healing in Rome. "

The cardinal's competence was based on his experience during the plague of 1656, when Pope Alexander VII commissioned him to manage the network of lazaros in Rome, which were hospitals where people were separated for isolation, quarantine and recovery.

The mass tombs marked C and F for the victims of the plague are visible in a map of the Basilica of San Paolo outside the walls of Rome in the manual of Cardinal Girolamo Gastaldi of 1684 containing the guidelines for responding to a plague. The cardinal's guidelines were based on his experience during the plague of 1656, when Pope Alexander VII commissioned him to manage the lazaros in Rome, where people were separated for isolation, quarantine and recovery. (Credit: CNS Photo / Courtesy Rare Book Collection, Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School.)

The rigorous forced containment system was the key to the protocols approved by the Pope's Congregation for Health, which Pope Urban VIII established in 1630 to take action whenever an epidemic struck.

While enacting and enforcing the norms was easier in the Papal States, since the powers of the church and the state were one, "a relationship of mutual collaboration" between the church and public institutions was often the norm elsewhere, although the two parts were not always synchronized or free of tension, said Marco Rapetti Arrigoni.

But whatever the circumstances in which church leaders found themselves plagues and pandemics, many still found ways to minister with creativity, courage and care, carefully following practices believed to protect themselves and others. from the contagion, he told the Catholic News Service.

To highlight how the current restrictions on public worship and the management of the sacraments have had numerous precedents in the history of the church and should not be considered conspiracy attacks against religion, Rapetti Arrigoni has published a series of detailed historical accounts online in Italian on breviarium.eu documenting the church's response to disease outbreaks over the centuries.

A map of the Trastevere district in Rome at the time of the plague epidemic of 1656 is seen in the 1684 manual of Cardinal Girolamo Gastaldi which contains guidelines for responding to a plague. At the top left is the Jewish Ghetto. The cardinal's guidelines were based on his experience during the plague of 1656, when Pope Alexander VII commissioned him to manage the lazaros in Rome, where people were separated for isolation, quarantine and recovery. (Credit: CNS Photo / Courtesy Rare Book Collection, Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School.)

He told CNS how the diocesan bishops were quick to introduce measures deemed effective at the time to stop the spread of the disease with restrictions on the assembly of the faithful and an increase in social distancing, hygiene, disinfection and ventilation.

The church had to find new ways to administer the sacraments and meet the needs of its faithful, he said in an email response to questions in early May.

In Milan, during the plague of 1576-1577, San Carlo Borromeo had votive columns and altars built at the crossroads so that the quarantined residents could venerate the cross on top of the column and participate in the Eucharistic celebrations from their windows.

The saint encouraged individuals and families to pray and arranged for the church bells to signal seven times during the day for a common prayer, preferably recited aloud from an open window.

He assigned some priests to go to certain neighborhoods. When a resident signaled the desire for the sacrament of reconciliation, the priest placed his portable leather stool outside the closed door of the penitent to hear the confession.

Throughout history, various tools have been used for some time to administer the Eucharist while ensuring social distancing, including long tongs or a flat spoon and a fistula or straw-like tube for consecrated wine or for the administration of the viaticum. Vinegar or a candle flame was used to disinfect the minister's utensils and fingers.

In Florence in 1630, Rapetti Arrigoni said, Archbishop Cosimo de 'Bardi had ordered priests to wear waxed clothes - in the belief that it would act as a barrier to infection - use a piece of cloth draped in front of them when offering Communion and affix a parchment curtain in the confessional between confessor and penitent.

He also said that one of his ancestors, Archbishop Giulio Arrigoni of Lucca, Italy, imposed difficult rules that proved useful in the past when cholera struck in 1854, as well as visiting the sick, distributing alms and providing spiritual comfort wherever possible.

The biggest mistakes made by communities, he said, were minimizing or incorrectly calculating the severity of the disease when cases first arose and subsequent inaction or poor response from the authorities.

There were also great risks in easing the restrictions too quickly, he said, as in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany when he was struck by the plague in 1630.

Public officials had argued for so long that a plan for a "light" quarantine was not implemented until January 1631 - more than a year after the first signs of illness were seen in the fall of 1629.

In the plan, numerous people were exempted from quarantine, in particular traders and other professionals, in order to prevent the collapse of the powerful Florentine economy, and many commercial premises, including hostels and taverns, were allowed to resume business after three months closing, he said.

The "plan" led to the epidemic of another two years, said Rapetti Arrigoni.

To this day, the Catholic Church and other religions play a vital role in taking care of those affected by disease and helping end epidemics, said Katherine Marshall, a researcher at the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Georgetown University Affairs and executive director of the Dialogue on the Development of World Faiths.

Trusted by their communities, religious leaders are critical to disseminating important health protocols, correcting false information, being behavioral patterns and influencing people's behavior, he said during a webinar on April 29 on the role of religion and the COVID pandemic. 19, sponsored by the International Partnership for Religion and Sustainable Development.

"Their roles can be falsely presented as" faith against science ", as" faith against secular "" authorities, "he said. But religious leaders can partner with governments and health experts and help build effective and coordinated efforts for relief and reconstruction.